Tutorial: Solving Continuous Domains

Tutorials > Solving Continuous Domains > Part 1

You are viewing the tutorial for BURLAP 3; if you'd like the BURLAP 2 tutorial, go here.

Introduction

In the Basic Planning and Learning tutorial we walked through how to use a number of different planning and learning algorithms. However, all the algorithms we covered were exclusively for finite state planning/learning problems and it is not uncommon in real world problems to have to deal with an infinite or continuous state space. Continuous state problems are challenging because there is an infinite number of possible states, which means you're unlikely to ever visit the same state twice. Since many of the previous algorithms rely on being able to exhaustively enumerate the states or revisit them multiple times to estimate a value function for each state, having an infinite number of states presents a problem that requires a different set of algorithms. For example, methods that generalize the value function to unseen "near by" states is one approach to handling continuous state space problems.

In this tutorial, we will explain how to solve continuous domains, using the example domains Mountain Car, Inverted Pendulum, and Lunar Lander, with three different algorithms implemented in BURLAP that are capable of handling continuous domains: Least-Squares Policy Iteration, Sparse Sampling, and Gradient Descent Sarsa Lambda.

As usual, if you would like to see all the finished code that we will write in this tutorial, you can jump to the Final Code section at the end, or you can get it from the burlap_examples respoistory.

Solving Mountain Car with Least-Squares Policy Iteration

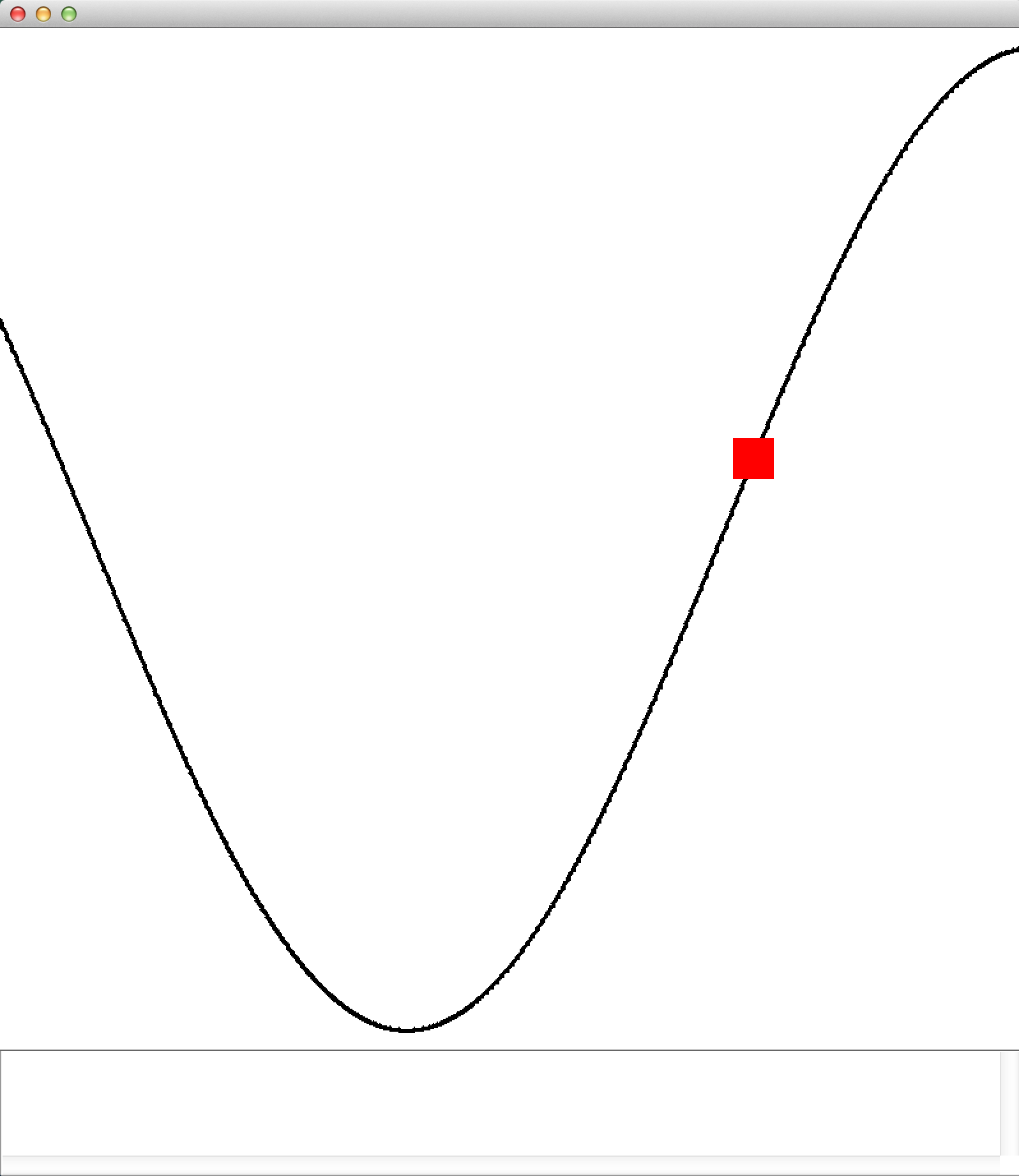

The Mountain Car domain is a classic continuous state RL domain in which an under-powered car must drive up a steep mountain. However, because the mountain is so steep, the car cannot just accelerate straight up to the top. Since car is in a valley, it can, however, make it to its destination by first moving backwards up the opposite slope, and then accelerate down to gain enough momentum to get up the intended slope.

An illustration of the Mountain Car problem, courtesy of Wikipedia.

To solve this problem, we will use Least-Squares Policy Iteration (LSPI). LSPI requires a collection of state-action-reward-state (SARS) transition tuples that are sampled from the domain. In some domains, like Mountain car, this data can be collected rather straight forwardly with random sampling of actions in the world. In other domains, the set of SARS data (and therefore how it is collected) is critical to getting good results out of LSPI, so it is important to keep that in mind.

LSPI starts by initializing with a random policy and then uses the collected SARS samples to approximate the Q-value function of that policy for the continuous state space. Afterwards, the policy is updated by choosing actions that have the highest Q-values (this change in policy is known as policy improvement). This process repeats until the approximate Q-value function (and consequently the policy) stops changing much.

LSPI approximates the Q-value function for its current policy by fitting a linear function of state basis features to the SARS data it collected, similar to a typical regression problem, which is what enables the value function to generalize to unseen states. Choosing a good set of state basis functions that can be used to accurately represent the value function is also critical to getting good performance out of LSPI. In this tutorial, we will show you how to set up Fourier basis functions and radial basis functions, which tend to be good starting places.

Lets start coding now. We'll begin by making a class shell, called ContinuousDomainTutorial. In it, we will create a different static methods that demonstrates solving each domain and algorithm in this tutorial, so we'll start with our method for solving Mountain Car with LSPI using Fourier basis functions (MCLSPIFB). As usual, we've preemptively included all imports that you'll use in the rest of this tutorial.

import burlap.behavior.functionapproximation.DifferentiableStateActionValue;

import burlap.behavior.functionapproximation.dense.ConcatenatedObjectFeatures;

import burlap.behavior.functionapproximation.dense.DenseCrossProductFeatures;

import burlap.behavior.functionapproximation.dense.NormalizedVariableFeatures;

import burlap.behavior.functionapproximation.dense.NumericVariableFeatures;

import burlap.behavior.functionapproximation.dense.fourier.FourierBasis;

import burlap.behavior.functionapproximation.dense.rbf.DistanceMetric;

import burlap.behavior.functionapproximation.dense.rbf.RBFFeatures;

import burlap.behavior.functionapproximation.dense.rbf.functions.GaussianRBF;

import burlap.behavior.functionapproximation.dense.rbf.metrics.EuclideanDistance;

import burlap.behavior.functionapproximation.sparse.tilecoding.TileCodingFeatures;

import burlap.behavior.functionapproximation.sparse.tilecoding.TilingArrangement;

import burlap.behavior.policy.GreedyQPolicy;

import burlap.behavior.policy.Policy;

import burlap.behavior.policy.PolicyUtils;

import burlap.behavior.singleagent.Episode;

import burlap.behavior.singleagent.auxiliary.EpisodeSequenceVisualizer;

import burlap.behavior.singleagent.auxiliary.gridset.FlatStateGridder;

import burlap.behavior.singleagent.learning.lspi.LSPI;

import burlap.behavior.singleagent.learning.lspi.SARSCollector;

import burlap.behavior.singleagent.learning.lspi.SARSData;

import burlap.behavior.singleagent.learning.tdmethods.vfa.GradientDescentSarsaLam;

import burlap.behavior.singleagent.planning.stochastic.sparsesampling.SparseSampling;

import burlap.domain.singleagent.cartpole.CartPoleVisualizer;

import burlap.domain.singleagent.cartpole.InvertedPendulum;

import burlap.domain.singleagent.cartpole.states.InvertedPendulumState;

import burlap.domain.singleagent.lunarlander.LLVisualizer;

import burlap.domain.singleagent.lunarlander.LunarLanderDomain;

import burlap.domain.singleagent.lunarlander.state.LLAgent;

import burlap.domain.singleagent.lunarlander.state.LLBlock;

import burlap.domain.singleagent.lunarlander.state.LLState;

import burlap.domain.singleagent.mountaincar.MCRandomStateGenerator;

import burlap.domain.singleagent.mountaincar.MCState;

import burlap.domain.singleagent.mountaincar.MountainCar;

import burlap.domain.singleagent.mountaincar.MountainCarVisualizer;

import burlap.mdp.auxiliary.StateGenerator;

import burlap.mdp.core.TerminalFunction;

import burlap.mdp.core.state.State;

import burlap.mdp.core.state.vardomain.VariableDomain;

import burlap.mdp.singleagent.SADomain;

import burlap.mdp.singleagent.common.VisualActionObserver;

import burlap.mdp.singleagent.environment.SimulatedEnvironment;

import burlap.mdp.singleagent.model.RewardFunction;

import burlap.mdp.singleagent.oo.OOSADomain;

import burlap.statehashing.simple.SimpleHashableStateFactory;

import burlap.visualizer.Visualizer;

import java.util.ArrayList;

import java.util.Arrays;

import java.util.List;

public class ContinuousDomainTutorial {

public static void main(String [] args){

MCLSPIFB();

}

public static void MCLSPIFB(){

//we'll fill this in in a moment...

}

}

Next we'll create an instance of the Mountain car domain and We'll use the standard reward function, physics, and termination conditions, so we don't need to adjust any parameters. (These return a reward of 100 when reaching the top of the mountain on the right side and zero everywhere else.)

MountainCar mcGen = new MountainCar(); SADomain domain = mcGen.generateDomain();

Other Mountain Car Parameters

We could have also changed parameters of the Mountain car domain, such as the strength of gravity, which is found in the physParams MountainCar data member, but without any modifications, it will automatically use the default parameterizations.

The next thing we will want to do is collect SARS data from the Mountain Car domain for LSPI to use for fitting its linear function approximator. For Mountain car, it is sufficient to randomly draw a state from the Mountain Car state space, sample a trajectory from it by selecting actions uniformly randomly, and then repeat the process over again from another random state. Lets collect data in this way until we have 5000 SARS tuple instances for our dataset. To accomplish this data collection, we can make use of a random StateGenerator to select random initial states, and perform random trajectory roll outs from them using a UniformRandomSARSCollector. Lets add code for that now.

StateGenerator rStateGen = new MCRandomStateGenerator(mcGen.physParams); SARSCollector collector = new SARSCollector.UniformRandomSARSCollector(domain); SARSData dataset = collector.collectNInstances(rStateGen, domain.getModel(), 5000, 20, null);

The MCRandomStateGenerator class provides a means to generate Mountain Car states with random positions and velocities. The collectNInstances methods will collect our SARS data for us. Specifically, we've told it to perform rollouts from states generated from our Mountain Car state generator for no more than 20 steps at a time or until we hit a terminal state. This process of generating a random state, rolling out a random trajectory for it, and collecting all the observed SARS tuples repeats until we have 5000 SARS instances. The null parameter at the end of the method call means we want it to create a new SARSData instance and fill it up with the results (and return it) rather than adding to an existing SARSData instance.

LSPI as a LearningAgent

In this case we're opting to collect all the data LSPI will use ahead of time. Alternatively, LSPI can be used like a standard learning algorithm (it does implement the LearningAgent interface) in which it starts with no data, acts in the world from whatever the world's current state is and reruns LSPI as it experiences more transitions (thereby improving the policy that it follows). However, this approach to acquiring SARS data is often not as efficient and there may be better means to acquire data when the agent is forced to experience the world as it comes rather than being able to manually sample the state space as we have in this tutorial. Therefore, if you are facing a problem in which you cannot manually control how states are sampled ahead of time, you may want to consider subclassing and overriding LSPI's runLearningEpisode method to use an approach that is a better fit for your domain. To learn more about how LSPI's default runLearningEpisode method is used, see the class's documentation.

The next thing we will want to define is the state basis features LSPI will use for its linear estimator of the value function. As noted previously, we will use Fourier basis functions. Fourier basis functions are very easy to implement without having to set many parameters, which makes it a good first approach to try.

Each Fourier basis function takes as input a state variable vector, where each element is a normalized scalar value. Each basis function corresponds to a state feature that LSPI will use for its linear function. The BURLAP FourierBasis class is an implementation of the DenseStateFeatures interface and will automatically make multiple Fourier basis functions based on the order you choose. The larger the order, the more basis functions (which grow exponentially with the dimension of input state feature vector) and the more fine grained the representation becomes, allowing for a more precise linear value function approximation.

Fourier basis features will ultimately give us a dense vectorized representation of states, but to construct them we will first need to turn our state objects into a normalized numeric vector of state variables. We can construct that using some standard BURLAP tools:

NormalizedVariableFeatures inputFeatures = new NormalizedVariableFeatures()

.variableDomain("x", new VariableDomain(mcGen.physParams.xmin, mcGen.physParams.xmax))

.variableDomain("v", new VariableDomain(mcGen.physParams.vmin, mcGen.physParams.vmax));

NormalizedVariableFeatures is an implementation of DenseStateFeatures, which provides a method to take an input State object and turn it into a double array. To construct it, it needs to be told which variable keys to use and what the numeric variable domain of that variable is. The double array output for states is then a array equal to the number of variables we specified with the normalized value according to the variable domain we gave it. Here, we're telling it to use the x and v variable keys from mountain car (specifying the x position and velocity of the car) and we gave it the variable domain by the values in our mountain car physics parameters.

With a method of producing a normalized state variable vector, we can now construct our Fourier basis features, using the FourierBasis class, an implementation of DenseStateFeatures itself.

FourierBasis fb = new FourierBasis(inputFeatures, 4);

In particular, we opted to use 4th order Fourier basis features, which is what the second parameter specifies.

Now lets instantiate LSPI on our Mountain Car domain and task with our Fourier basis functions; tell it to use a 0.99 discount factor; set its SARS dataset to the dataset we collected; and run LSPI until the weight values of its fitted linear function change no more than 10^-6 between iterations or until 30 iterations have passed.

LSPI lspi = new LSPI(domain, 0.99, new DenseCrossProductFeatures(fb, 3), dataset); Policy p = lspi.runPolicyIteration(30, 1e-6);

One thing to note is that we gave LSPI DenseCrossProductFeatures on our constructed FourierBassis object. Note that FourierBasis features are just a mapping from states to features. But to actual learn a control mechanism, LSPI needs state-action features; that is, separate features for each action so that the value of actions can be modeled, from which a policy can be constructed. It is not uncommon in RL to first define a state feature representation, and then construct state-action features by taking the cross product of those features with each action. That is precisely what the DenseCrossProductFeatures will do: it takes as input the state features and creates a cross product of them with the actions actions. The '3' argument we provided it tells it how many actions there are.

After LSPI has run until convergence, we will want to analyze the policy is produced. To analyze the resulting policy, we could roll it out and load an EpisodeSequenceVisualizer, as we have in prior tutorials. But for fun, lets watch it in real time.

To visualize the animated results, we can simply grab the existing visualizer from the domain (MountainCarVisualizer), create a SimulatedEnvironment in which to evaluate the policy, and add a VisualActionObserver to the to the environment. Note that we can add an EnvironmentObserver to a SimulatedEnvironment, because it implements the EnvironmentServerInterface (otherwise we could use an EnvironmentServer wrapper for Environment instances that do not implement the observer interface). Specifically, we'll let it run for five policy rollouts.

Visualizer v = MountainCarVisualizer.getVisualizer(mcGen);

VisualActionObserver vob = new VisualActionObserver(v);

vob.initGUI();

SimulatedEnvironment env = new SimulatedEnvironment(domain,

new MCState(mcGen.physParams.valleyPos(), 0.));

env.addObservers(vob);

for(int i = 0; i < 5; i++){

PolicyUtils.rollout(p, env);

env.resetEnvironment();

}

System.out.println("Finished");

We also set the initial state of the environment to start in the bottom of the valley. We can get the x position value for the bottom of the valley, but calling the valleyPos() method on mountain car physics parameters object (we also set the initial velocity to zero).

If you now run the main method, you see at the start a bunch of print outs to the terminal specifying the maximum change in weight values after each policy iteration. When the change is small enough, LSPI will end and you'll get a window animating the the mountain car task using the results of LSPI. That is, you should see something like the below image.

A screen cap from the animation of the Mountain car task

Although the settings we used are pretty robust to failure, it is possible (even if unlikely) that the car won't make it to the right side, which indicates that LSPI failed to find a good policy from the valley of the hill. LSPI can fail if your dataset collection happened to be unluckily bad. However, if you rerun the code (resulting in a a new random data collection), you should find that it works.

Radial Basis Functions

Before we leave Mountain Car and LSPI for the next example, lets consider running LSPI on Mountain Car with a different kind of state basis features; specifically, lets consider using radial basis functions. A radial basis function is defined with a "center" state, a distance metric, and a bandwidth parameter. Given an input query state, the basis function returns a value between 0 and 1 with a value of 1 when the query state has a distance of zero from the function's "center" state. As the query state gets further away, the basis function's returned value degrades to a value of zero. The sensitivity of the basis function to the distance is defined by its bandwidth parameter; as the bandwidth value increases, the less sensitive the function is to distance (that is, a large bandwidth will result in it returning a value near 1 even when the query state is far away).

A set of state features defined by a set of radial basis functions distributed across the state space gives an approximation of where a given state is. You can think of the set of radial basis function outputs as compressing the state space. As a consequence, a common approach to using radial basis functions is set up a coarse multi-dimensional grid over the state space with a separate radial basis function centered at each intersection point of the grid. BURLAP provides us tools to easily accomplish such a construction of radial basis functions.

Lets start by a creating a new method for running LSPI with radial basis functions. It will look almost identical to the previous Fourier Basis LSPI method we created, except instead of defining Fourier basis functions, we'll define radial basis functions. For the moment, the code below will create an instance of a radial basis features (RBFFeatures), but we will need to add code to actually add the set of radial basis functions it uses. Also note that we moved the initial state object instantiation to earlier in the code, because we will use it to help define the center states of the radial basis functions we will create. The differences are highlighted with comments in the code.

public static void MCLSPIRBF(){

MountainCar mcGen = new MountainCar();

SADomain domain = mcGen.generateDomain();

MCState s = new MCState(mcGen.physParams.valleyPos(), 0.);

NormalizedVariableFeatures inputFeatures = new NormalizedVariableFeatures()

.variableDomain("x", new VariableDomain(mcGen.physParams.xmin, mcGen.physParams.xmax))

.variableDomain("v", new VariableDomain(mcGen.physParams.vmin, mcGen.physParams.vmax));

StateGenerator rStateGen = new MCRandomStateGenerator(mcGen.physParams);

SARSCollector collector = new SARSCollector.UniformRandomSARSCollector(domain);

SARSData dataset = collector.collectNInstances(rStateGen, domain.getModel(), 5000, 20, null);

RBFFeatures rbf = new RBFFeatures(inputFeatures, true);

//we will add rbfs next

LSPI lspi = new LSPI(domain, 0.99, new DenseCrossProductFeatures(rbf, 3), dataset);

Policy p = lspi.runPolicyIteration(30, 1e-6);

Visualizer v = MountainCarVisualizer.getVisualizer(mcGen);

VisualActionObserver vob = new VisualActionObserver(v);

vob.initGUI();

SimulatedEnvironment env = new SimulatedEnvironment(domain, s);

env.addObservers(vob);

for(int i = 0; i < 5; i++){

PolicyUtils.rollout(p, env);

env.resetEnvironment();

}

System.out.println("Finished");

}

You'll notice that we passed "true" to our RBFeatures constructor. The true flag indicates that that the feature database should include a constant feature that is always on. This provides a Q-value "y intercept" value to the linear function that will be estimated. This is often not necessary, but it doesn't hurt.

Since RBF features compute distances between states, it too will operate on a numeric vector of state variables. Here we've opted to use our NormalizedVariableFeatures class to provide that since we don't want different domain sizes of the variables to affect the state distance calculation.

To construct a set of radial basis functions over a grid, we will first want to generate the states that lie at the intersection of grid points on a grid. To construct the set of states, we will make use of the FlatStateGridder class in BURLAP. FlatStateGridder allows you to set up arbitrarily specified grids over a state space and return the set of states that lie on the intersection points of the grid. FlatStateGridder can even do things like include constant values for some variables. (There is also an OOStateGridder for gridding OO-MDP states.) For our current purposes, we just want a fairly simple grid that spans the full state space of Mountain Car. To use StateGridder, it does require that the State objects implement MutableState, which our mountain car states do (as do the states for just about all standard BURLAP domains).

To get the set of states that span a 5x5 grid over the car position and velocity attributes (for a total of 25 states), add the below code right below the instantiation of the RBFFeatures. If you want to know how to set up a more specific grid (e.g., an asymmetric grid like a 3x7), see the class's documentation

FlatStateGridder gridder = new FlatStateGridder()

.gridDimension("x", mcGen.physParams.xmin, mcGen.physParams.xmax, 5)

.gridDimension("v", mcGen.physParams.vmin, mcGen.physParams.vmax, 5);

List<State> griddedStates = gridder.gridState(s);

Notice that the gridInputState method requires an example State object? An example state is required because it tells the gridder (1) what the input State Java class is; and (2) only will grid over the values you specified with calls to gridDimension, leaving any other variables in the input state left unchanged in the gridded states.

Now that we have a bunch of states distributed over a uniform grid of the state space, we will want to create radial basis functions centered at each of those states. Specifically, we'll use Gaussian RBFs with a 0.2 bandwidth parameter and a Euclidean distance metric; BURLAP has implementation for both these. However, to define the "center" point of these states, we'll need to convert the state into its numeric state vector representation, which we provided by passing each of our Gridded states through the NormalizedVariableFeatures object we constructed.

DistanceMetric metric = new EuclideanDistance();

for(State g : griddedStates){

rbf.addRBF(new GaussianRBF(inputFeatures.features(g), metric, 0.2));

}

Our final Mountain Car LSPI radial basis function method should now look like the below.

public static void MCLSPIRBF(){

MountainCar mcGen = new MountainCar();

SADomain domain = mcGen.generateDomain();

MCState s = new MCState(mcGen.physParams.valleyPos(), 0.);

NormalizedVariableFeatures inputFeatures = new NormalizedVariableFeatures()

.variableDomain("x", new VariableDomain(mcGen.physParams.xmin, mcGen.physParams.xmax))

.variableDomain("v", new VariableDomain(mcGen.physParams.vmin, mcGen.physParams.vmax));

StateGenerator rStateGen = new MCRandomStateGenerator(mcGen.physParams);

SARSCollector collector = new SARSCollector.UniformRandomSARSCollector(domain);

SARSData dataset = collector.collectNInstances(rStateGen, domain.getModel(), 5000, 20, null);

RBFFeatures rbf = new RBFFeatures(inputFeatures, true);

FlatStateGridder gridder = new FlatStateGridder()

.gridDimension("x", mcGen.physParams.xmin, mcGen.physParams.xmax, 5)

.gridDimension("v", mcGen.physParams.vmin, mcGen.physParams.vmax, 5);

List<State> griddedStates = gridder.gridState(s);

DistanceMetric metric = new EuclideanDistance();

for(State g : griddedStates){

rbf.addRBF(new GaussianRBF(inputFeatures.features(g), metric, 0.2));

}

LSPI lspi = new LSPI(domain, 0.99, new DenseCrossProductFeatures(rbf, 3), dataset);

Policy p = lspi.runPolicyIteration(30, 1e-6);

Visualizer v = MountainCarVisualizer.getVisualizer(mcGen);

VisualActionObserver vob = new VisualActionObserver(v);

vob.initGUI();

SimulatedEnvironment env = new SimulatedEnvironment(domain, s);

env.addObservers(vob);

for(int i = 0; i < 5; i++){

PolicyUtils.rollout(p, env);

env.resetEnvironment();

}

System.out.println("Finished");

}

If you now point your main method to call the MCLSPIRBF method, you should see similar results as before, only this time we've used radial basis functions!

Now that we've demonstrated how to use LSPI on the mountain car domain with Fourier basis functions and radial basis functions, we'll move on to a different algorithm (Sparse Sampling) and a different domain (the Inverted Pendulum).