Tutorial: Basic Planning and Learning

Tutorials (v1) > Basic Planning and Learning > Part 3

- Introduction

- Creating the class shell

- Initializing the data members

- Setting up a result visualizer

- Planning with BFS

- Planning with DFS

- Planning with A*

- Planning with Value Iteration

- Learning with Q-Learning

- Learning with Sarsa(λ)

- Live Visualization

- Value Function and Policy Visualization

- Experimenter Tools and Performance Plotting

- Conclusion

Planning with BFS

One of the most basic deterministic planning algorithms is breadth-first search, which we will demonstrate first. Since we will be testing a number of different planning and learning algorithms in this tutorial, we will define a separate method for using each planning or learning algorithm and then you can simply select which one you want to try in the main method of the class. We will also pass each of these methods the output path to record its results. Before we begin, lets import a few more packages and classes that we will use for all the planning and learning algorithms.

import burlap.behavior.singleagent.learning.*; import burlap.behavior.singleagent.learning.tdmethods.*; import burlap.behavior.singleagent.planning.*; import burlap.behavior.singleagent.planning.commonpolicies.GreedyQPolicy; import burlap.behavior.singleagent.planning.deterministic.*; import burlap.behavior.singleagent.planning.deterministic.informed.Heuristic; import burlap.behavior.singleagent.planning.deterministic.informed.astar.AStar; import burlap.behavior.singleagent.planning.deterministic.uninformed.bfs.BFS; import burlap.behavior.singleagent.planning.deterministic.uninformed.dfs.DFS; import burlap.behavior.singleagent.planning.stochastic.valueiteration.ValueIteration;

With those classes imported, lets start by defining the BFS method.

public void BFSExample(String outputPath){

if(!outputPath.endsWith("/")){

outputPath = outputPath + "/";

}

//BFS ignores reward; it just searches for a goal condition satisfying state

DeterministicPlanner planner = new BFS(domain, goalCondition, hashingFactory);

planner.planFromState(initialState);

//capture the computed plan in a partial policy

Policy p = new SDPlannerPolicy(planner);

//record the plan results to a file

p.evaluateBehavior(initialState, rf, tf).writeToFile(outputPath + "planResult", sp);

}

The first 'if' condition regarding the outputPath is just to make sure the string is well formed and ends with a '/' and is not very important. The next part of the method actually creates an instance of the BFS planning algorithm, which itself is a subclass of the DeterministicPlanner class. To instantiate BFS, it only requires a reference to the domain, the goal condition for which it should search, and the hashing factory. Planning is then performed by simply calling the planFromState method on the planner and passing it the initial state form which it should plan. After this method completes, the plan will be stored inside the BFS object.

It might seem a little strange that this method does not simply return a sequence of actions or something of the sort. The reason it does not is because not all planning and learning algorithms compute a sequence of actions. In particular, stochastic planners and planners that compute solutions for non-terminating tasks compute a policy rather than a sequence of actions. Because the DeterministicPlanner class is also a subclass of the OOMDPPlanner class, which is used as a superclass for all planning algorithms, the common planFromState method does not return anything.

Since the planFromState method does not explicitly return the plan results, we will instead capture it using a Policy class, which is more general for capturing solutions with any number of planners and allows flexibility in determining how the solution is captured. For capturing the plan solution of deterministic planners, the SDPlannerPolicy class may be used, whose constructor takes as a parameter a DeterministicPlanner object. Since many deterministic planners will compute a sequence of actions to take from the initial state, the SDPlannerPolicy will only be defined for states along the path to the solution. If you wanted something slightly more general that will return an answer for states not on the solution path, you could instead use the DDPlannerPolicy class which will compute the solution using the specified planner if the planner had not yet computed the solution for the state for which the policy was queried.

Once you have a Policy object, you can extract an entire episode from it by calling the evaluateBehavior method. There are a few different versions of the evaluateBehavior method which take different parameters to determine the analysis and stopping criteria. In this case, however, we are passing it the initial state from which the policy should start being followed, the reward function used to assess the performance and the the termination function which specifies when the policy should stop. The method will return an EpisodeAnalysis object which will contain all of the states visited, actions taken, and rewards received when following that policy. You can investigate these individual elements of the episode if you like, but for this tutorial we're just going to save the results of this episode to a file and then use the offline visualizer we previously defined to view it. An EpisodeAnalysis object can be written to a file by calling the writeToFile method on it and passing it a path to the file and the state parser to use. Note that the method will automatically append a '.episode' extension to the file path if you did not specify it yourself.

And that's all you need to code to plan with BFS on a defined domain and task!

Using the EpisodeSequenceVisualizer GUI

Now that the method to perform planning with BFS is defined, add a method call to it in your main method.

public static void main(String[] args) {

BasicBehavior example = new BasicBehavior();

String outputPath = "output/"; //directory to record results

//run example

example.BFSExample(outputPath);

//run the visualizer

example.visualize(outputPath);

}

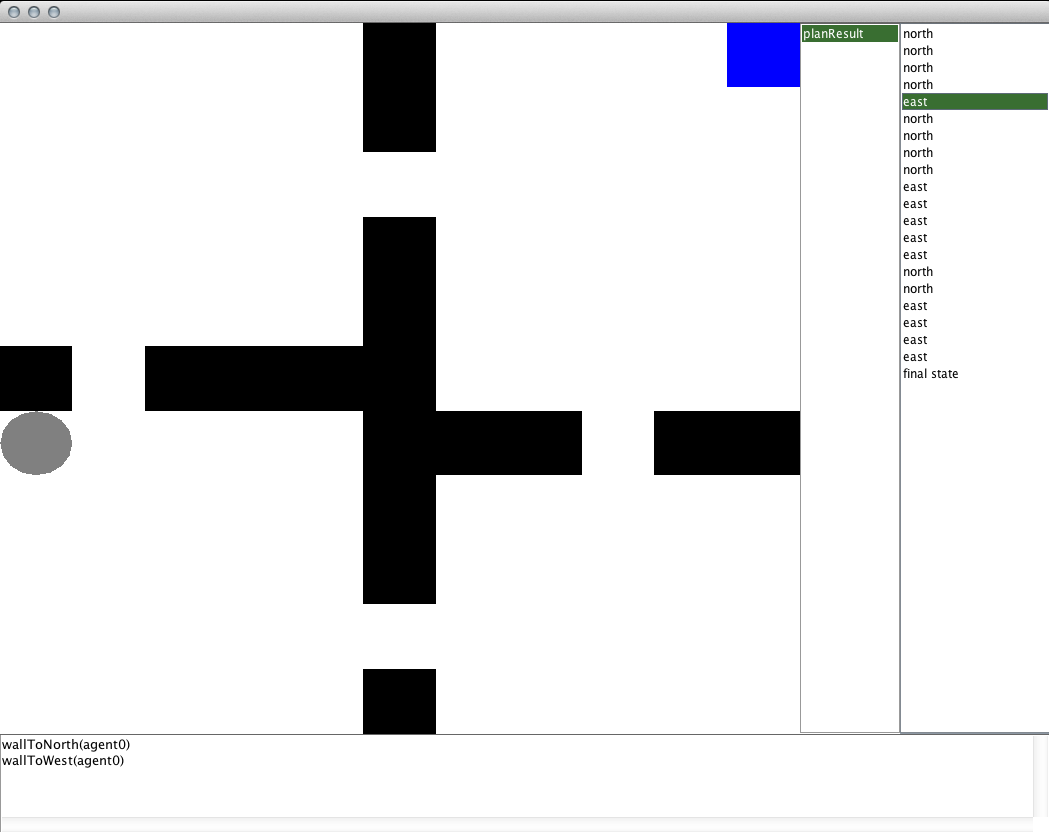

And with the planning method hooked up, run the code! Because the task is simple, BFS should find a solution very quickly and print to the standard output the number of nodes it expanded in its search. Following that, the GUI should be launched for viewing the EpisodeAnalysis object that was recorded to a file. You should see something like the below image appear.

The main panel in the center of the window is used to render the current state selected. The text box at the bottom of the window will list all of the propositional functions that are true in that state. The leftmost list on the right side of the window lists all of the episode files that were recorded in the directory passed to the EpisodeSequenceVisualizer constructor. After selecting one of those instances, the list of actions taken in the episode are listed on the right-most list. Note that the action corresponds to the action that will be taken in the state that is currently visualized, so the result of the action will be seen in the next state. In the GridWorldDomain visualizer, the black cells represent walls, the grey circle represents the agent, and the blue cell represents the location object that we made.

Planning with DFS

Another common search-based planning algorithm is depth-first search (DFS). Define the below method to provide a means to solve the task with DFS.

public void DFSExample(String outputPath){

if(!outputPath.endsWith("/")){

outputPath = outputPath + "/";

}

//DFS ignores reward; it just searches for a goal condition satisfying state

DeterministicPlanner planner = new DFS(domain, goalCondition, hashingFactory);

planner.planFromState(initialState);

//capture the computed plan in a partial policy

Policy p = new SDPlannerPolicy(planner);

//record the plan results to a file

p.evaluateBehavior(initialState, rf, tf).writeToFile(outputPath + "planResult", sp);

}

You will notice that the code for DFS is effectively identical to the previous BFS code that we wrote, only this time the DeterministicPlanner is instantiated with a DFS object instead of BFS object. DFS has a number of other constructors that allow you to specify other parameters such a depth limit, or maintaining a closed list. Feel free to experiment with them.

After you have defined the method, you can call it from the main method like we did the BFS method and visualize the results in the same way. Since DFS is not an optimal planner, it is likely that the solution it gives you will be much worse than the one BFS gave you!

Planning with A*

One of the most well known optimal search-based planning algorithms is A*. A* is an informed planner because it takes as input an admissible heuristic which estimates the cost to the goal from any given state. We can also use A* to plan a solution for our task as long as we also take the additional step of defining a heuristic to use. The below code defines a method for using A* with a Manhattan distance to goal heuristic.

public void AStarExample(String outputPath){

if(!outputPath.endsWith("/")){

outputPath = outputPath + "/";

}

Heuristic mdistHeuristic = new Heuristic() {

@Override

public double h(State s) {

String an = GridWorldDomain.CLASSAGENT;

String ln = GridWorldDomain.CLASSLOCATION;

ObjectInstance agent = s.getObjectsOfTrueClass(an).get(0);

ObjectInstance location = s.getObjectsOfTrueClass(ln).get(0);

//get agent position

int ax = agent.getDiscValForAttribute(GridWorldDomain.ATTX);

int ay = agent.getDiscValForAttribute(GridWorldDomain.ATTY);

//get location position

int lx = location.getDiscValForAttribute(GridWorldDomain.ATTX);

int ly = location.getDiscValForAttribute(GridWorldDomain.ATTY);

//compute Manhattan distance

double mdist = Math.abs(ax-lx) + Math.abs(ay-ly);

return -mdist;

}

};

//provide A* the heuristic as well as the reward function so that it can keep

//track of the actual cost

DeterministicPlanner planner = new AStar(domain, rf, goalCondition,

hashingFactory, mdistHeuristic);

planner.planFromState(initialState);

//capture the computed plan in a partial policy

Policy p = new SDPlannerPolicy(planner);

//record the plan results to a file

p.evaluateBehavior(initialState, rf, tf).writeToFile(outputPath + "planResult", sp);

}

There are two main differences between this method and the methods that we wrote for BFS and DFS planning. The smaller difference is that the A* constructor takes the reward function and heuristic as parameters. The reward function is needed because it is what A* uses to keep track of the actual cost of any path it is exploring.

Note

A* is an algorithm that operates on costs and is not an algorithm that can work with negative costs. BURLAP in general represents state-action evaluations as rewards, rather than costs. However, a cost can be represented as a negative reward; therefore, the reward function provided to A* should return negative values. If the reward function returns any positive values, A* will not function properly. Since our example's reward function returns only negative values (it returns -1 for every state-action pair), our reward function will work fine with A*.

The bigger difference between the previous planning code and A* is in defining the heuristic, which we will explain in more detail. First note that the heuristic follows a standard interface for which we have may an anonymous java class. The h method of the class is passed a state object and the method should return the estimated reward to the goal from that state. Since we have opted to use the Manhattan distance as our heuristic, this will involve computing the distance between the agent position and the location position (for which we will assume there is only one). To compute this difference, the method will first need to extract the agent object instance and the location object instance out of the state, which is done in lines 16 and 17. Specifically, the getObjectsOfTrueClass method of a state will return the list of objects in the state that belong to the class with the specified name. Since the task we are solving will only have one agent object and one location object, we can then just return the 0th indexed objects in each of those respective lists. Lines 20-25 then extract the integer values for the X and Y attributes of both objects. Once those attribute values are retrieved, the Manhattan distance is computed and returned in lines 28-30. Note that the negative distance is returned, because our reward function returns -1 for each step.

With the rest of the code being the same, you can have the main method call the A* method for planning and view the results in the usual way!