Tutorial: Basic Planning and Learning

Tutorials > Basic Planning and Learning > Part 1

- Introduction

- Creating the class shell

- Initializing the data members

- Setting up a result visualizer

- Planning with BFS

- Planning with DFS

- Planning with A*

- Planning with Value Iteration

- Learning with Q-Learning

- Learning with Sarsa(λ)

- Live Visualization

- Value Function and Policy Visualization

- Experimenter Tools and Performance Plotting

- Conclusion

You are viewing the tutorial for BURLAP 2; if you'd like the BURLAP version 1 tutorial, go here.

Introduction

The purpose of this tutorial is to get you familiar with using some of the planning and learning algorithms in BURLAP. Specifically, this tutorial will cover instantiating a GridWorld domain bundled with BURLAP, creating a task for it, having the task solved with Q-learning, Sarsa learning, BFS, DFS, A*, and Value Iteration. The tutorial will also show you how to visualize these results in various ways using tools in BURLAP. The take home message you should get from this tutorial is that using different planning and learning algoritms largely amounts to just changing the algorithm object you instantiate, with everything else being the same. You are encouraged to extend this tutorial on your own using some of the other planning and learning algorithms in BURLAP.

At the conclusion section of this tutorial, you will find all of the code we created, so if you'd prefer to jumpt right in, only coming back to this tutorial as questions arise, feel free to do so!

Creating the class shell

For this tutorial, we will start by making a class that has data members for all the domain and task relevant properties. In the tutorial we will call this class "BasicBehavior" but feel free to name it to whatever you like. Since we will also be running the examples from this class, we'll include a main method. For convenience, we have also included at the start all of the class imports you will need for this tutorial. If you have a good IDE, like IntelliJ or Eclipse, those can auto importing the classes as you go so that you never have to write an import line yourself.

import burlap.behavior.policy.GreedyQPolicy;

import burlap.behavior.policy.Policy;

import burlap.behavior.singleagent.EpisodeAnalysis;

import burlap.behavior.singleagent.auxiliary.EpisodeSequenceVisualizer;

import burlap.behavior.singleagent.auxiliary.StateReachability;

import burlap.behavior.singleagent.auxiliary.performance.LearningAlgorithmExperimenter;

import burlap.behavior.singleagent.auxiliary.performance.PerformanceMetric;

import burlap.behavior.singleagent.auxiliary.performance.TrialMode;

import burlap.behavior.singleagent.auxiliary.valuefunctionvis.ValueFunctionVisualizerGUI;

import burlap.behavior.singleagent.auxiliary.valuefunctionvis.common.ArrowActionGlyph;

import burlap.behavior.singleagent.auxiliary.valuefunctionvis.common.LandmarkColorBlendInterpolation;

import burlap.behavior.singleagent.auxiliary.valuefunctionvis.common.PolicyGlyphPainter2D;

import burlap.behavior.singleagent.auxiliary.valuefunctionvis.common.StateValuePainter2D;

import burlap.behavior.singleagent.learning.LearningAgent;

import burlap.behavior.singleagent.learning.LearningAgentFactory;

import burlap.behavior.singleagent.learning.tdmethods.QLearning;

import burlap.behavior.singleagent.learning.tdmethods.SarsaLam;

import burlap.behavior.singleagent.planning.Planner;

import burlap.behavior.singleagent.planning.deterministic.DeterministicPlanner;

import burlap.behavior.singleagent.planning.deterministic.informed.Heuristic;

import burlap.behavior.singleagent.planning.deterministic.informed.astar.AStar;

import burlap.behavior.singleagent.planning.deterministic.uninformed.bfs.BFS;

import burlap.behavior.singleagent.planning.deterministic.uninformed.dfs.DFS;

import burlap.behavior.singleagent.planning.stochastic.valueiteration.ValueIteration;

import burlap.behavior.valuefunction.QFunction;

import burlap.behavior.valuefunction.ValueFunction;

import burlap.domain.singleagent.gridworld.GridWorldDomain;

import burlap.domain.singleagent.gridworld.GridWorldVisualizer;

import burlap.oomdp.auxiliary.common.SinglePFTF;

import burlap.oomdp.auxiliary.stateconditiontest.StateConditionTest;

import burlap.oomdp.auxiliary.stateconditiontest.TFGoalCondition;

import burlap.oomdp.core.Domain;

import burlap.oomdp.core.TerminalFunction;

import burlap.oomdp.core.objects.ObjectInstance;

import burlap.oomdp.core.states.State;

import burlap.oomdp.singleagent.RewardFunction;

import burlap.oomdp.singleagent.SADomain;

import burlap.oomdp.singleagent.common.GoalBasedRF;

import burlap.oomdp.singleagent.common.UniformCostRF;

import burlap.oomdp.singleagent.common.VisualActionObserver;

import burlap.oomdp.singleagent.environment.Environment;

import burlap.oomdp.singleagent.environment.EnvironmentServer;

import burlap.oomdp.singleagent.environment.SimulatedEnvironment;

import burlap.oomdp.statehashing.HashableStateFactory;

import burlap.oomdp.statehashing.SimpleHashableStateFactory;

import burlap.oomdp.visualizer.Visualizer;

public class BasicBehavior {

GridWorldDomain gwdg;

Domain domain;

RewardFunction rf;

TerminalFunction tf;

StateConditionTest goalCondition;

State initialState;

HashableStateFactory hashingFactory;

Environment env;

public static void main(String[] args) {

//we'll fill this in later

}

}

If you're already familiar with MDPs in general, the importance of some of these data members will be obvious. However, we will walk through in detail what each data member is and why we're going to need it.

GridWorldDomain gwdg

A GridWorldDomain is a DomainGenerator implementation for creating grid worlds.

Domain domain

A Domain object is a fundamental class for defining problem domains. In short Domain objects define how states in a problem are represented

and how the physics of the problem environment work. BURLAP represents states in a problem as a collection of objects, each with their own state. Therefore, a Domain object defines a set of

attributes, object classes, propositional functions, and actions (along with the actions transition dynamics) that define the problem.

RewardFunction rf

A RewardFunction is an interface that has a method for returning a double valued reward for any given state-action-state

sequence. This is a fundamental component of every MDP and its what an agent tries to maximize. That is, the goal

of an agent is acquire as much reward from the world as possible.

TerminalFunction tf

A common form of MDPs are episodic MDPs: MDPs that end in some specific state or set of states.

A typical

reason to define an episodic MDP is when there is a goal state the agent is trying to reach. In such cases, the goal

state is a terminal state, because once the agent reaches it, there is nothing left to do.

Inversely, some states may be fail states that prevent the agent continuing; these too would be terminal states.

There may also be other reasons to provide termination states, but whatever you reason may be, a

TerminalFunction is an interface with a boolean method that defines which states are terminal states.

StateConditionTest goalCondition

Not all planning algorithms are designed to maximize reward functions. Many

are instead defined as search algorithms that seek action sequences that will cause the agent to reach specific goal states.

A StateConditionTest is an interface with a boolean method that takes a state as an argument similar to a

TerminalFunction, only it can be used as a means to specify any kind of state test rather than just terminal states. In this tutorial we will

use it to specify goal states for planning algorithms that search for action sequences to reach goals rather than

planning algorithms that try to maximize reward.

State initialState

To perform any planning or learning, we will generally need to specify an initial state

from which to perform it and to reason about the different states that the agent encounters as it acts. In BURLAP, we use the State interface for providing this information, which has various methods for accessing information about the state. In particular, BURLAP uses the object-oriented MDP representation formalism, which represents states as a collection of objects, each which belongs to an object class and has a set of attributes. This is a very powerful representation that can handle a number of different kinds of problems. In this tutorial, you will not need to think much about the internal structure of the state, because we will use the GridWorldDomain class to produce initial state objects for us. For more information on it, see the State Java doc, or read the Building a Domain tutorial.

HashableStateFactory hasingFactory

In this tutorial, we will be covering planning and learning algorithms that solve problems that have a finite number of states that the algorithm can enumerate and reason about directly (these are sometimes called tabular algorithms). To enumerate and look up different states efficiently, algorithms typically store them in a hash-backed data structure (like a HashMap, or a "dictionary" for those of you who are new to Java). Using these data structures requires a means to compute hash codes for States and, depending on the kind of problem, some ways of computing hash codes may be more efficient than others. Furthermore, It is not uncommon that your may want handle state equality in different ways depending on the problem (for example, maybe you want to perform an abstraction that ignores certain attribute values or objects in the state).

For these reasons, BURLAP allows you to provide tabular algorithms a HashableStateFactory. A HashableStateFactory has a method that takes as input a State object and returns a HashableState. A HashableState stores a reference to the source state and can compute an efficient hash code for the state and perform state equality checks with other HashableState instances.

More on HashableStateFactory

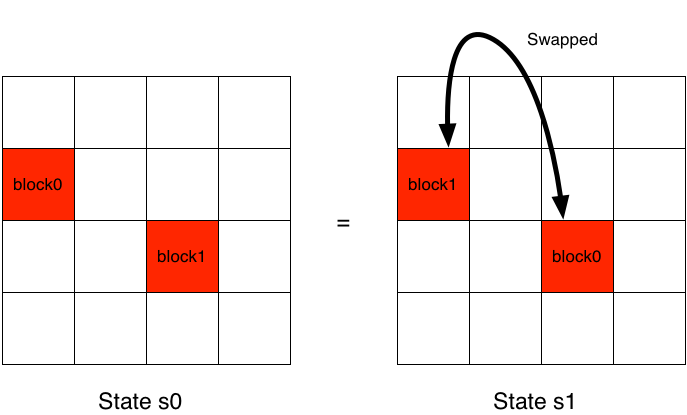

While BURLAP provides a number of different HashableStateFactory classes for handling common ways of performing hashing and state equality checking (see the statehashing package Java doc for a list), when it doubt you can typically use the SimpleHashableStateFactory, which we will use in this tutorial. One of the advantages of SimpleHashableStateFactory is that when it checks state equality between two states (or computes the hash code for a state), it will by default be object identifier independent. Object identifier independence means that when a state is made up of multiple objects of the same class, the order of the objects and the names that identify them does not affect whether two states are equal. That is, as long as the states have a set of equivalent objects, they will be considered the same state. For example, consider a state (s0) made up of two block objects (block0 and block1) that are defined by spatial position information. Now imagine a new state (s1) that is the result of swapping the positions of block0 and block1. Even though the object identifiers associated with the block positions (block0 and block1) are different between s0 and s1, these really are the same state and when equality is object identifier independent they will be considered equal. The below illustration helps clarify this property.

Sometimes the name of objects does matter, for example in relational domains in which the goal state refers to a specific object. In these cases, SimpleHashableStateFactory can be told in a constructor not to use object identifier independence. And since many of the HashableStateFactory classes in BURLAP inherit from SimpleHashableStateFactory, they can all have object identifier independence toggled.

Environment env

Learning algorithms address a problem in which the agent observes its environment, makes a decision, and then observes how the environment changes. This is a challenging problem because initially, an agent will not know how the environment works or what a good decision is, but must live with the consequences of their decision. To facilitate the construction of this problems, all learning algorithms in BURLAP (algorithms that implement the LearningAgent interface), interact with an implementation of the Environment interface. In BURLAP, there exists a SimulatedEnvironment implementation for when the environment dynamics are defined by a BURLAP Domain, but since Environment is an interface, you can easily implement your own version if you need a BURLAP agent to interact with external code or systems (for example, robotics, which BURLAP has an extension for supporting on ROS.).